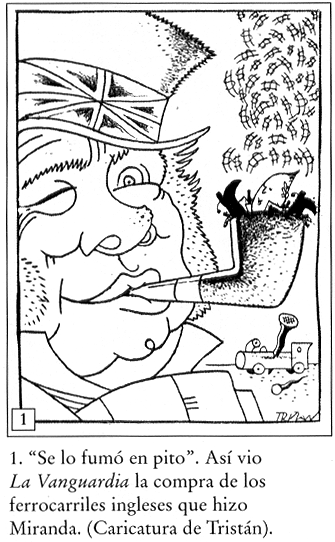

ARGENTINE RAILWAY NATIONALISATION:

NOTES FROM THE PRESS AND COMPANY REPORTS, 1906 TO 1955.

SUMMARY: Those who blame Perón for having nationalised Argentina's foreign-owned railways

and those who worship him for having done so are both seriously mistaken. Neither Perón nor anyone in his government had made any innovation.

They only followed precedents set by a previous administration and bowed to foreign pressure.

Two developments induced railway shareholders to "canvass" the possibility of nationalisation. First, a 1931 agreement with labour unions allowed wage

cuts on condition of (a) the retention of supernumerary workers and (b) the suspension of dividends. The agreement became official policy by the Presidential Award of 1934

that extended the suspension of dividends to preference shares and attenuated the wage cuts by turning them into refundable "retentions." By the early 1940s government

allowed tariff increases on condition that they be applied to wage payments. Thus the railwaymen had de facto obtained a first mortgage on railway revenue. Second, bilateral

Anglo-Argentine trade agreements provided for artificially low exchange values of the peso and exchange controls. Thus the peso cost of fuel, other supplies, and what

remittances of interest and dividends the railways remained able to make was increased by nearly 50 per cent.

While the shareholders became willing to sell and the government was willing to buy, successive governments did not act until the British government, pressured by the US, first to sell the railways

to American interests, and second

to return to convertibility, sought to solve its balance of payments, exchange control and food supply problems by putting the railways up for sale. The early post-war trade

and exchange policies of the US and the UK were pursued world-wide resulting in a wholesale divestiture of UK assets abroad that Argentina could not avoid. However,

Argentina negotiated the hardest terms it could get: unprecedented gold guarantees, increased commodity prices, ex gratia payments, etc.

The British were in a dire situation. They had obtained a much needed US credit of 3.75 billion dollars ($3,750,000,000)

only on condition of a speedy return to free convertibility of the pound sterling.

That raised the spectre of an Argentine Government withdrawal of their £150 million of blocked sterling at the Bank of England, exchanged for (at the then current rate of exchange) into US$600,000,000.

That would have meant a haemorrhage of a major part of the new US credit which had to be avoided at all costs. The cost was the abandonment of British-owned railways in Argentina as a means to wipe out the Argentine credit at the Bank of England.

The nationalisation of British-owned railways in Argentina must not be viewed in isolation

of the British Government's eagerness to achieve a liquidation of British business interests abroad.

That desire was so strong that, in the end, the purchase price of £150 million was not financed by exhaustion of Argentine deposits in London but by

a gift of £10 million from the British Government, a British credit of £100 million, and only £40 million of Argentine money. The credit was an advance payment for future deliveries of Argentine products,

deliveries made at previously increased prices of beef and maize.

Expropriation terms mandated by Argentine Law (payment of "recognised capital" plus 20 per cent.) were never considered and much less applied. By waiting till after the

law had allegedly expired (which it did not, only the tax concessions granted by it had a sunset clause) Argentina got the railways for much less: for the value of one year's

worth of a bilateral trade balance. Whereas Sao Paulo share and bond holders got more than their nominal capital, holders of Argentine railway securities got about 60 per

cent, and about 75 per cent of what the law had mandated. Unhappy shareholders were threatened with dire consequences if they rejected the deal.

The above may be sufficient to dispel the belief that Perón and Miranda had a leading role in railway nationalisation.

It is more correct to say that they followed and made the best they could of a British initiative which was as inevitable as it had been pursued

by the British in many other countries besides Argentina.

In later years there was much occasion to regret the nationalisation with a repeat of Perón's flippant talk of a high price for old iron, but that was not the issue. What was regrettable was the persistence with

war-time labour, exchange, and railway rate policies rooted in the 1930s that nearly ruined the foreign-owned railways and finally ruined the government railways.

Finally, it must be noted that the money paid by Argentina in nationalisation was not all immediately received by railway shareholders. The French-owned companies continued operating in Argentina until the 1950s.

Shareholders in British-owned companies saw the liquidations of their companies drag on until 1964.

Those who resided abroad (outside the UK) had their liquidation payments frozen in blocked sterling accounts for several years.

Early appetite

Largely out of disappointment with the guarantee system and a desire to construct extensions of guaranteed lines there

have been some early expropriation projects, none of which prospered:

In 1882, Deputy Carlos Bouquet introduced a bill to expropriate the Central Argentine Railway, and in 1883 Deputy Torcuato Gilbert

did the same in regards to the East Argentine Railway. Gilbert's project advanced to the point were President Julio A. Roca

and Minister Bernardo de Irigoyen sent a bill to Congress for the expropriation of the East Argentine Railway.

(The South American Journal, 31 August 1881, page 11; Cámara de

Diputados, Diario de Sesiones, 11 June 1883, pages 248-249; 15 June 1883, pp. 310-313; 27 July 1883, pages 749-750.)

Celestino Pera's project

A Deputy [Celestino Pera] presented a project to Congress, by which a tax of one cent on every dollar of railway revenue would be collected, the proceeds to be used to buy

railway shares, and the dividends then also applied to buying shares. Thus he figured the railways would be completely nationalised in 60 years.

(South American Journal, 13 October 1906, page 398)

The [1907] Budget Report advised the creation of a reserve fund to be applied to the purchase of railway shares of private companies, so as ultimately to nationalise

the Argentine system.

(The Annual Register, a Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad for the Year 1906, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1907, page 472.)

Repentant Bolsheviks at the Buenos Aires Chamber of Commerce?

In 1917 Argentine merchants had been agitating for railway nationalization, studied the question, and presented their conclusions to the Minister of Public Works, an extract of which was reprinted by

Alejandro E. Bunge in his Ferrocarriles Argentinos, Contribución al estudio del patrimonio nacional, Buenos Aires, 1918, pages 432-35:

Respecto de la expropiación resultan interesantes y sugestivas, — aun cuando no coincidimos en todo acerca de este punto, — las observaciones que hace el "Comité Nacional del Comercio", en el

estudio presentado al Ministerio de Obras Públicas de la Nación, el 7 de noviembre de 1917.

"Aparte de conocerse por todos las enormes pérdidas soportadas

por el ferrocarril del Estado, la operación financiera sobre la base de

las tarifas actuales resulta a todas luces inconveniente para los intereses públicos que tendrían que soportar una pérdida anual de $ oro 60.000.000, carga demasiado pesada para el erario público que

tendría que salvarse con impuestos que irían a gravitar sobre determinadas industrias llamadas en esencia a sostener el enorme déficit anual.

"El capital emitido por los ferrocarriles hasta el 31 de diciembre de 1914 era aproximadamente de 1.324.090.073 oro sellado.

"La expropiación tendría que efectuarse por esa suma más la del 20 % que casi todas las concesiones autorizan como indemnización, lo que representaría la suma de $ oro 1.588.908.087.

Esta operación demandaría un empréstito de $ o|s. 1.700 millones, si se tratase de un empréstito de 6 % de interés y uno de amortización acumulativa colocado en las mejores condiciones, o sea a 93 %

libre de gastos.

"Si el interés del empréstito de 5 a 1 %, el tipo en que se tomaría neto, neto para el gobierno, no sería superior a 85 %, lo que representaría la suma aproximada de $ o|s. 1.840 millones.

"La primera operación de $ o|s. 1.700 millones demandaría un servicio anual de $ o|s. 119 millones, y la segunda operación, la de 110.400.000 $ o|s., en tanto que el producto anual de los ferrocarriles ha

sido:

| 1910 |

$ o|s |

110.941.406 |

| 1911 |

" " |

116.782.267 |

| 1912 |

" " |

132.059.613 |

| 1913 |

" " |

140.113.204 |

| 1914 |

" " |

114.742.638 |

| Representando sus gastos la suma de: |

| 1910 |

$o|s |

65.926.627 |

| 1911 |

" " |

71.447.103 |

| 1912 |

" " |

82.641.737 |

| 1913 |

" " |

87.274.512 |

| 1914 |

" " |

78.831.242 |

| Lo que significa una utilidad de: |

| 1910 |

$o|s |

45.011.779 |

| 1911 |

" " |

45.335.164 |

| 1912 |

" " |

49.417.876 |

| 1913 |

" " |

52.838.692 |

| 1914 |

" " |

35.911.396 |

"De esto se deduce que con las tarifas actuales todas las entradas, haciendo abstracción de los gastos, serían apenas suficientes para pagar el servicio del empréstito, que tomando el menor servicio, o sea

el 5 y 1 % y la mayor entrada, la de 1913, de $ o|s 140.113.204, daría una pérdida mínima anual de $ o|s. 57.561.308.

"Si la operación se redujere a un determinado ferrocarril pasaría igual cosa, así, por ejemplo, si tomaran aislados o conjuntamente los tres ferrocarriles que han redituado más, como ser: el Sud, Oeste y

Central Argentino.

"Para expropiar el F. C. Sud se necesitarían 290.000.000 de $ o|s., o sea un empréstito de 310.300.000 de $ o|s. al 6 % de interés y uno de amortización, o uno de 333.500.000 $ o|s. de 5 y 1, lo que

obligaría a un servicio de 21.721.000 $ o|s. o 20.010.000, cuando el producido del mejor año, o sea de 1913, ha sido de 30.627.492 $ o|s con 17.724.861 $ o|s. de gastos, o sea una utilidad de 12.903.131

$ oro; de modo que en el mejor de los casos habría un déficit anual de más de 7.000.000 de $ oro sellado.

"Para el Oeste la expropiación sería de 153.000.000 $ o|s., con un empréstito de 5 y 1 %, lo que requeriría un servicio anual de $ o|s. 9.180.000, cuando el producido del mejor año ha dado la suma de

14.088.812 $ o|s. con 8.031.335 $ o|s. de gastos y una utilidad de $ o|s. 6.057.479, lo que equivale a decir un déficit de $ o|s. aproximado a 4.200.000 anuales.

"Para el Central Argentino, ella llegaría a 324.000.000 $ o|s. con un servicio de $ o|s. 19.440.000; habiendo sido el mayor producido del último quinquenio el de $ o|s. 32.734.821 contra 19.135.594 $ o|s.

de gastos que representa sólo una utilidad de $ o|s. 13.599.227, de modo que con esa base se produciría un déficit anual aproximado de 6.000.000 $ oro sellado.

"Son éstas, señor Ministro, las causas que nos han determinado a realizar este estudio, que va sin duda alguna a disipar creencias equívocas y prejuicios injustificables.

"Debemos hacer también una sincera aclaración y es la que antes de entrar al análisis de la situación de las empresas, creíamos como la generalidad que: a) la situación de ellas era próspera, b) que los

rendimientos efectivos de las mismas eran ocultados, y c) que la legislación existente les permitía una libertad de acción inconciliable con el decoro y los intereses generales del país.

"Hoy en posesión de todos los detalles, nos satisfacemos en manifestar nuestro error y en evidenciarlo a todas luces, máxime cuando la determinante de una u otra opinión no obedecía sino a una

verdadera convicción."

The last two paragraphs are quite revealing but the misconceptions remained and were repeated for propaganda reasons:

Promotion of socialism by American anti-British propaganda

The men in charge of public affairs in the Argentine are perfectly fair and just and considerate

as regards the stranger who has invested money within their gates. We have no complaint to make, as

I have said before. People sometimes say to me: "In the Argentine you may get a Socialist Government.

You know there are Socialists there who say we are earning gigantic profits in the Argentine Railways".

There was a scandalous paper which came out in the Argentine some time ago, issued by Americans, —

citizens of the United States— in which they said: "These English railways are coining money: they have

one statement of accounts to show to the Argentines, and they have another statement of accounts

concealing immense wealth which they show to their shareholders in London." (Laughter).

Well, gentlemen, you know, to your sorrow, that is not so. (Hear, hear and laughter).

(VISCOUNT ST. DAVIDS at the Buenos

Ayres & Pacific Railway meeting held 18 December 1919)

An Argentine Railway Expropriation.

According to La Nación of Tucumán, a speech made by Engineer Uttinger on the occasion of his

being nominated Administrator of the State Railways, has attracted considerable attention. He

referred to an entire reorganisation of the administrative staff of the railways, and added that it

was an evident necessity, and a measure was to be put into practice without delay either to

expropriate the Central Cordoba Railway or to make a fusion of the State lines with it in order

that the lines of the nation should extend right into the Federal Capital. One of his first

administrative intentions, he stated, was to join up the Antilla branch with the main line at

Rosario de la Frontera, and to complete the works of the inter-Provincial line with Catamarca

connecting it with that of the Central Cordoba at La Cocha.

(Railway News, 12 May 1917, page 554)

Bid and ask prices for the Central Railway of Chubut

The [Central Railway of Chubut] Company was said to have asked 20,000 gold pesos per kilometre of line but that the Argentine Government had offered to buy the line for

only 13,968 gold pesos per km.

(The Review of the River Plate, July 14, 1922, page 83)

Nationalisation of the Central Railway of Chubut

The Argentine Government purchased the Central Railway of Chubut, ad referendum of Congress, for the price of 1,950,000 gold pesos [18,571 per km.], 487,000 gold

pesos in cash and the balance at 12, 18 and 24 months with 6% interest.

(The Economist, 16 September 1922)

[Congress delayed authorisation of the purchase. In the interim the railway was leased for £21,280 per annum]

State Railways made no cash payment in respect of rent since April, 1930. The total amount owing June 30, 1931 was m$n 387,634 (£33,841 at par). The Company received

in respect of this debt 7% 180-day renewable promissory notes for m$n 243,750.

During the year, the State Railways finished laying 75 cm. gauge track on the original metre gauge line between Port Madryn and Trelew, and rolling stock of the former

gauge is now in use over the whole system.

(Central Railway of Chubut, Report of the Directors for 1930-31)

Por Ley 11.860 se aprueba el contrato de compra-venta del Ferrocarril Central del Chubut por 1.950.000 pesos oro sellado más el importe de arrendamientos atrasados.

(Boletín Oficial 12.063, 28 de agosto de 1934)

The railway, pier and maritime plant with a book value of £326,771 were sold for £271,300 in 4% Argentine "Roca Bonds" delivered in 1935 and not negotiable for two years.

The bonds were disposed of in October of 1936.

Holders of £95,800 in 6% bonds received £99,562 on 31 May 1937. Holders of £200,000 in shares received £153,953 in instalments.

The liquidation of the company was completed on 31 July 1947.

The Montevideo Agency of La Prensa reported on August 10 that the Uruguay Government intended to

purchase the Central Uruguay Railway and that negotiations with Mr. Grindley, the General Manager,

were proceeding satisfactorily.

(The Review of the River Plate, 15 August 1930, page 40.)

A Forecast

It must . . be borne in mind that, sooner or later, and probably sooner, the ever-growing tendency towards

nationalisation will lead to a conflict of interests which is bound to affect the situation of the railways in Argentina.

Again and again, the Socialist deputies, with Catonian persistency, call for reconsideration of the various enactments

dealing with the railway tariffs, while already, with the recent increases scarce a month ago, a private proposal has been

laid before Congress by one of the deputies, Mr. Bauschi, calling for a reduction of freight on sundry items of livestock

and goods traffic classified as being calculated to benefit agricultural, pastoral, or mining interests. It is probable that

Argentina does but follow her destiny in this matter of giving special preference to national as opposed to foreign

initiatives, but one sometimes doubts whether London interests fully realise that this trend of events must be followed

sympathetically and closely if its subsequent development is not to prove unpleasantly abrupt. Abrupt, that is to say, to

those who have not followed step by step the reasoning and the ambitions of the present-day young Argentine, who, be

it said en passant, is both technically and intellectually on a far higher plane than his immediate predecessors.

(The Economist, 28 October 1922, page 806, posted at Buenos Aires 26 September 1922).

Search for State Railway access to Buenos Aires by nationalisation of a French-owned railway:

Un actionnaire demande ce qui'il y a de vrai dans les bruits de rachat de la Compagnie que l'on

entende continuellement.

Monsieur le Président fait connaître qu'il y a eu, en effet, des pourparlers avec le Gouvernement

Argentin qui nous a faite des propositions, mais celles-ci ne nous ayant pas paru acceptables tant

au point de vue économique qu'au point de vue juridique, la question est restée en suspense

jusqu'à présent.

(Compagnie Générale de Chemins de fer dans la Province de Buenos-Ayres,

Procès-verbal de l'Assemblée du 20 Décembre 1922.)

There is talk...of an important line now in private hands to be acquired by the Argentine Government and merged in the State Railway system...Argentine credit is sufficiently

good that, if the Government so decides, it can acquire the particular railway to which we refer and, no doubt, could acquire a large proportion and

ultimately the whole of the railway system...those interested in Argentina, provided such a proposal were to take practical shape, would be well advised to consider how their

interest would be affected...It is important to bear in mind the somewhat alarming experiences to which property owners, and particularly railway shareholders and the

owners of scrip in various transport undertakings, were subjected during the recent Administration.

(The Statist, 11 November 1922, page 684)

The Cordoba Central Railway

As reported by the Chairman in his address at the Ordinary General Meeting of the Company held on the 30th October, 1924, the Directors were asked, and stated, the terms

upon which they would be prepared to recommend to the Proprietors the transfer of the Company's property to the Argentine Government. As, however, after the expiry of

some 12 months, the Government had not come to any decision in the matter, and there appeared to be no immediate prospect of their being able to do so, the Directors

considered it inadvisable to allow the offer to remain open any longer, and it accordingly lapsed.

(Cordoba Central Railway, Report of the Directors for the Year 1924-25, pages 5-6)

Prevention of American control of Argentine railways

In May of 1929 Senator Diego Luis Molinari and President Hipólito Irigoyen became

alarmed by the prospect of American takeover of Argentine railways. Malcolm Robertson, British Ambassador to Argentina, was asked for assistance to

prevent American control of Argentine railways.

(Foreign Office document 371/13460.)

Notice was given that at the Ordinary General Meeting of the Argentine Great Western Railway Company, Limited, held at Winchester House, 100 Old Broad Street, in the

City of London, on Monday, the 28th day of October, 1929, that

"the following Extraordinary Resolution will be proposed which, if passed by the requisite majority, will be submitted to a subsequent extraordinary General Meeting for

confirmation as a Special Resolution, viz.:

RESOLUTION.

That the Articles of Association be altered in manner following :—

[a] By adding at the end of Article 2 the following words :—

(G) The expression "foreigner" means any person who is not of British or Argentine nationality, and the expression "foreign corporation" means any corporation other than a

corporation established under and subject to the laws of some part of His Majesty's Dominions or the Argentine Republic and having its principal place of business in those

Dominions or in the Argentine Republic. The expression "Corporation under foreign control" includes :—

(a) A corporation of which the majority of the Directors or persons occupying the position of Directors by whatever name called are foreigners.

(b) A corporation shareholders in which holding shares or stock conferring a majority of the votes are foreigners or foreign corporations or persons who hold directly or

indirectly for foreigners or foreign corporations.

(c) A corporation which is by any other means whether of a like or of a different character in fact under the control of foreigner or foreign corporations.

(d) A corporation the executive whereof is a corporation within (a) (b) or (c).

[b] By inserting next before Article 62 the following new Article to be numbered 61A:—

61A. Every person or corporation seeking to be registered as a member of the Company shall before being registered as such member make and deliver to the Company a

declaration in writing (if eligible to do so) in a form to be approved by the Board of the Company that the person or corporation so seeking to be registered as aforesaid is not

a foreigner or a foreign corporation or a corporation under foreign control and does not hold the shares or stock in respect of which he or it so seeks to be registered as

aforesaid for or in trust for or on behalf or under the control of a foreigner or foreigners or foreign corporation or foreign corporations or a corporation under foreign control

and if such person or corporation or corporations shall fail to make such declaration or if after being called upon so to do by the Board he or it shall fail to prove to the

satisfaction of the Board that he or it is not a foreigner or a foreign corporation or a corporation under foreign control or does not hold such shares or stock for or in trust for

or on behalf or under the control of a foreigner or foreigners or foreign corporation or foreign corporations or corporation or corporations under foreign control such person or

corporation shall be registered as a member of the Company in a special part of the Register (hereinafter called "the Special Register") and no member of the Company who

is registered in the Special Register shall be entitled to vote either on a show of hands or on a poll and whether in person or by proxy at any General Meeting of the Company.

A majority of the Board may also at any time certify in writing that there is in their opinion reason to believe that any share or stock in the Company is held by or for or in

trust for or on behalf or under the control of a foreigner or foreigners foreign corporation or foreign corporations or corporation or corporations under foreign control and

thereupon the Board shall call upon the holder of such shares or stock to prove to its satisfaction that the share or stock in question is not so held and upon such certificate as

aforesaid being signed the name of the holder of such share or stock shall be entered in the Special Register and shall remain so entered until the time when such proof as

aforesaid is given or until the share or stock referred to in such certificate is duly registered in the name of some other person or corporation.

The succeeding Articles numbered 62 to 69 (both inclusive) shall be read subject to this Article. Subject as aforesaid all shares or stock of any class of the Company shall

notwithstanding that such shares or any of them or such stock or any part thereof are or shall be held by or for or in trust for or on behalf or under the control of a foreigner or

foreign corporation or corporation under foreign control rank as to capital dividends and in all other respects pari passu with other shares or stock of the same class.

[c] By adding at the end of Article 72 the words:—

"all of whom shall be of British or Argentine nationality."

As explained in Argentine Great Western Railway, Report of the Directors for the Year 1928-29, presenting Alterations to Articles of Association for consideration by the shareholders at the

General Meeting, pages 8-9:

"The general effect of these alterations will be that they will preclude the possibility of any foreign shareholders, other than Argentine nationals, obtaining control of the

management of the Company. There is to-day virtually no foreign holding in the Company. The Directors believe that it is a matter of national importance that the control of

the company, subject to the limitation mentioned above, should remain as at present, and they confidently invite the support of the members for the scheme."

[Identically worded resolutions were passed in the same year by the

Central Argentine, Cordoba Central, Pacific, Southern and Western railway companies.

These measures taken by British-owned Argentine railway companies were not taken only by them but followed those of several other British enterprises. See The Economist

of June 8, June 15 and 22 June 1929, pages 1292, 1350 and 1386.]

Colonel Josiah Wedgwood, M.P. (Labour), was opposed to these disenfranchisements, considering the action to be unwarranted.

(The Review of the River Plate, 21 June 1929, pages 9, 11.)

Foreign (other than Argentine) shareholders were disenfranchised as a precautionary measure [taken by the Buenos Ayres and Pacific Railway Company in June, 1929] to

ward off American take-over....Paradoxically, this American interest followed after, and may even have been stimulated by, the disenfranchisement.

(The Economist, July 13, 1929, page 80)

Mesures de Défense prises par les Compagnies Anglaises contre les capitaux étrangers.— Monsieur Bustos Morón rend compte dans sa lettre du 14 Mai que des Compagnies de Chemin

de fer Anglaises, en vue de parer à l'éventualité d'une main mise des capitaux Nord-Américains sur les actions de leurs Sociétés pour en prendre le contrôle, ont fait modifier leurs Statuts

en vue de supprimer le droit de vote aux actionnaires de nationalité autre que Anglaise ou Argentine.

D'autre part, Monsieur Bustos Morón signale qu'il a été question du rachat par des capitaux Nord-Américains de la concession Selva, de Rosario à Mendoza, ce qui pourrait être une

indication au sujet des projets des capitalistes des Etats-Unis en Argentine.

(Cie. du chemin de fer de Rosario à Puerto-Belgrano, Conseil d'administration, Procès Verbal de la Séance du 5 juillet 1929.)

Intentions des Américains et des Compagnies Anglaises au sujet des réseaux français en Argentine.— Dans la même lettre, le Directeur rend compte qu'au cours d'un autre entretien

qu'il a eu avec Monsieur Leslie, il a été question des rumeurs qui circulent au sujet des tentatives de groupes Nord-Américains pour s'emparer du contrôle des Chemins de fer Argentins

et notamment des réseaux français depuis que les Compagnies Anglaises ont prise de mesures pour empêcher l'accaparement de leurs actions. Le Directeur a retiré l'impression que

pour éviter cette éventualité d'ingérence de capitaux Américains les Compagnies Anglaises ont déjà pensé sérieusement à prendre l'initiative d'une opération de ce genre.

Le Conseil décide de se renseigner sur les conditions du marché des actions de la Compagnie a fin de savoir si celui-ci ne présente rien d'anormal et au besoin d'étudier les moyens de

parer a quelques tentatives de main mise sur la Compagnie.

(Cie. du chemin de fer de Rosario à Puerto-Belgrano, Conseil d'administration, Procès Verbal de la Séance du 31 juillet 1929.)

Exit of an Anglo-Argentine

"...ya en el año 1929...noté síntomas alarmantes de que el tiempo próspero para el negocio

ferroviario había pasado en el país y que se aproximaban tiempos muy difíciles. Ignoro si otros

accionistas habrán pensado o hecho lo mismo, pero por mi parte, después de reunir acciones de un valor nominal de cien libras esterlinas, durante mucho tiempo,

creí llegado el momento de deshacerme de ellas, vendiéndolas a 112 libras."

Las causas del deterioro vistas por el autor fueron la Ley de Vialidad N° 11.658, falta de coordinación de

transportes, devaluación del peso y control de cambios, crecientes cargas sociales apenas cubiertas por

tardíos aumentos de tarifas.

El 26 de abril de 1934 el Ferrocarril Sud "decidió no extender más sus vías, limitándose a mantener las existentes y tomó la decisión

definitiva de no levantar más capital en acciones ordinarias de la empresa."

(Arthur H. Coleman, Mi vida de ferroviario en la Argentina, 1887-1948, Bahía Blanca, Talleres Gráficos Panzini, 16 de mayo de 1949, págs. 576 y 586.)

Noblesse oblige ...

Nous avons à vous signaler par ailleurs que, pour l'année 1936, les Pouvoirs Publics ont accordé aux Compagnies de Chemins de fer un change spécial pour les transferts autorisés, qui

est supérieur de 5 % au taux officiel d'achat payé par le Gouvernement Argentin: mais en contre-partie les Compagnies ont dû consentir un rabais sur les tarifs de transports de maïs.

(Compagnie Française de Chemins de Fer de la Province de Santa-Fé, Rapport du Conseil d'Administration sur l'exercice 1935-1936)

At 30 June 1938 the Cordoba Central Railway had a book value of £21,506,94 and £332,478 in stores of coal and other materials. This was sold for £700,000 in cash, £8,800,000 in 4% State Railway Bonds, and

an undisclosed sum for stores. At 30 June 1939 the State Railways were still owing £133,351 for stores.

The State Railway bonds were redeemed prematurely on 1 Nov. 1944.

Investors received an estimated amount of £9,926,099, most of which was paid by 1945. Liquidation was completed 31 August 1964.

Canvassing the Government

The Association of Investment Trusts and Insurance Companies requested Baring Brothers & Co. to approach President Justo through their Buenos Aires agent. The

association wanted to determine whether the Argentine Government would consider some scheme for nationalising the railways. It wanted to know whether the Argentines

would accept gradual acquisition of a substantial interest in the British owned companies. Baring Brothers thought this could be accomplished in a number of ways. The

British companies could convert themselves into Argentine companies and express their capital in pesos rather than in £ sterling. Baring also suggested a scheme in which

the Argentine Government would buy outright 30 to 40 per cent of the equity...paying for the purchase in 3 or 4% bonds...As an alternative, Baring Bros. proposed that the

Argentine Government consider a plan to buy the British railways on the open market...

(Henderson to Eden, 20 January 1937, and Foreign Office Minutes, 20 July 1936, Public Record Office, Foreign Office, 371/20598, 371/19761 cited by W. R. Wright,

British-owned Railways in Argentina, Texas, 1974, pp. 211-12.)

British-Argentine Railway Committee

In 1936 the British-owned railways formed a "British-Argentine Railway Committee" in Buenos Aires primarily to better respond to

increasingly restrictive railway policies of the Argentine Government. The Committee was composed of the chairmen and other members

of the Local Boards of the British-owned railways. Its chairmanship rotated annually among the Argentine chairmen of the local boards.

A similar committee was formed among the directors in London. During the 1940s that committee evolved by interlocking directorships

among the boards of the four broad-gauge railways. Thus only two or three directors were needed to accompany British Government missions

to Buenos Aires and to negotiate the sale of the British-owned railways. This followed the dissolution in 1936 of Jointco, an older committee formed in 1933 that included representatives of the French-owned railways.

(Info. from several Directors' Reports.)

Nationality of Personnel of Privately Owned Railways

According to the Instituto de Estudios Económicos del Transporte (supported by railways and

housed in the Railway Clearing House), the employees and workmen composing the personnel of

the Southern, Western, Central Argentine, Pacific and Córdoba Central railways number 90,792.

Of these 49,519, or 55 per cent. are Argentines, whilst 41,273, or 45 per cent are foreigners. This

proportion is very close to that of the adult male inhabitants of the country. The male inhabitants

of the country of ages between twenty and sixty years number 2,900,000. Of these approximately

1,700,000 or 59 per cent. are native born citizens, whilst the remaining 1,200,000, or 41 per cent

are foreigners.

Of the 41,273 foreigners employed by the five railway companies referred to, only 1,650 are

British — that is to say citizens of the country of origin of capital of the railways. These 1,650

persons represent only 1.8 per cent of all the personnel employed by the five railway companies.

As regards the proportion of the different nationalities listed in a complete census of railway

staff, the most representative, after the Argentine, are the Italians and Spaniards. In point of fact,

the number of workpeople of each nationality corresponds more or less, in the proportionate

sense, to the percentage of each foreign community to the total foreign population of the country.

In other words the possibility of obtaining employment on the railways is, according to

nationality, purely and simply a matter of the relative number of persons of each nationality in

the entire adult population of the Republic.

(The Review of the River Plate, 4 December 1936, page 33. Of course, this does not address the nationalists'

complaint of under-representation at the higher railway management levels. However, given the small size of the

native-born population and the correspondingly small number of native high-school and university graduates, a

correction of the lamented under-representation would have forced government departments and railways to hire

foreign professionals.)

Nationalisation of the Transandine Railway

4. As the shareholders have been informed by circular, during the past year discussions have taken place between the Argentine Government

and the Company for the future of the Railway, arising out of the decree by the Government [of 30 December 1935] ordering the repair of the portion of the line destroyed in the flood of 1934.

The Government subsequently decided to take control of the line and to become responsible for its reconstruction.

These negotiations resulted in an agreement being signed in June last by the Executive Power and the representative of the Company

embodying the terms upon which the Argentine Government will acquire the Railway.

The terms of this agreement were set out in the circular to the shareholders of the 24th June last and are subject to the approval of the Argentine Congress

and the Debenture and Shareholders of the Company.

Congress has not yet dealt with the matter, but it is hoped that the agreement will receive its consideration and approval in near future.

(Argentine Transandine Railway Company, Report of the Directors and Statement of Accounts for the Year Ended June 30, 1937, pages 6-7)

The final terms agreed on 8 June 1937, were as follows:

£75,000 cash plus £675,000 in 4% Argentine Railway Sterling Bonds guaranteed by Government and blocked against sale for 5 years.

£383,985 of 5% (Govt. Bond) Debenture remained a Government debt and were exchanged for Argentine 5% Bonds on which the Stock was secured.

£225,000 Deferred Shares held by Government were cancelled.

Law No. 12.573 of February 20, 1939 authorized the purchase for a maximum of m$n 5.614.489.

The State Railways took possession on 1 September 1939.

On 30 June 1937 the Transandine Railway had a book value of £2,484,444, plus £55,516 in stores and £21,140 owing to it by Government for freight and fares.

The investors received an estimated £860,603, most of which had been paid by 14 August 1946.

The liquidation was completed on 3 March 1960.

Nationalisation of the Cordoba Central Railway

[Because of dust-bowl conditions in the US, some Argentine railways had the benefit of carrying the maize exports of two years] The revival of railway receipts indirectly

caused the recent partial strike on the Cordoba Central Railway. Under the Award of the President of the Republic of October 23, 1934, which was accepted by the

companies and the railwaymen, it was agreed that wages should be cut until such time as the surplus of receipts over expenses should reach a certain level. This level has

been attained by the other companies but not by the Cordoba Central...The men of the latter company...saw no reason for their own less happy lot.

The strike, which was unauthorised by the railwaymen's own leaders, was called after the strikers' representatives had been interviewed by the Minister of Public Works. The

Government is about to issue a decree restoring the cuts. In the meantime, efforts are being made in several political quarters, Opposition as well as Government, to persuade

Congress to approve the purchase of the Cordoba Central Railway by the State without delay.

(The Economist, 3 July 1937, page 19, posted by the Argentine correspondent June 19)

9. In the month of December, 1936, terms were provisionally agreed with the Government of the Argentine Republic, subject to the approval of the Stockholders of the

Company, for the purchase of the Company's undertaking by the State, the consideration to be £8,000,000 (nominal) 4 per cent. State Railway Sterling Bonds guaranteed by

the Nation, and £700,000 in cash, plus a sum in respect of Stores on hand.

Towards the end of that month the Government submitted a Bill to Congress for authorising the purchase of the railway.

10. Partial stoppages of work by the Company's employees occurred in the month of June last, the men demanding the restoration of the salaries and wages cuts made by

virtue of the Presidential Award of October, 1934. As a consequence the Argentine Government intervened and ordered that the cuts be suspended, and undertook to bear the

cost involved.

These arrangements covered a period of four months from the 1st June to the 30th 5eptember, 1937, during which time it was considered by the Government that Congress

would have come to a decision as to the purchase by the State of the Company's undertaking. The ordinary session of Congress, however, terminated on the 30th

September last without dealing with the matter, and as the Government did not extend the period of their undertaking, further stoppages of work on the part of the men

ensued on the 15th October. The Argentine Government again intervened, and proposed that the State Railways should assume the direction of the working of the

railway for a period of up to 12 months, undertake to satisfy the claims of the men, and guarantee to the Company practically the same net earnings as those realised during

the past financial year. Should, in the meantime, sanction of Congress be obtained to the purchase of the railway, the option for which is being continued, the Government

will make up the difference between the said net earnings and an amount equivalent to 4 per cent. on the agreed purchase price.(1)

The Board accepted the Government's proposal, and normal service was re-established throughout the railway on the 4th November.

The sale contract remains subject to the approval of the Stockholders.

(Cordoba Central Railway, Report of the Directors and Statement of Accounts for the Year Ended June 30, 1937, pages 4-5, paragraphs 9 and 10)

On February 11th the Government sent to Congress a long message explaining their motives in taking over the Cordoba Central Railway. The message recapitulates the

Government's policy of ultimately taking over all the privately owned railways, announced last year. The nationalisation of the railways, it considers, would strengthen the

bases of Argentine social peace. The action of the Government in taking over the Cordoba Central Railway by decree has been criticised in Argentina as an encroachment

upon the powers and privileges of Congress, and it is apparent that the purpose of the recent message is to persuade Congress to endorse the action of the Executive with

regard to the railways without delay. The delay is due to Alvearista [Radical] opposition to President Ortiz [Concordancia].

(The Economist, February 26, 1938, page 443, "Correspondence from Argentina," posted February 12)

The message could not have been clearer: "la incorporación de las líneas del Central Córdoba a la red del Estado, . . . importa un primer paso . . . de lo que ha de constituir, sin duda, nuestra

orientación ferroviaria del porvenir . . . Restituir al dominio pleno de la Nación . . . servicios públicos esenciales . . . es la política que debe seguirse en el futuro

. . . el transporte por ferrocarril no debe tener otra tarifa que la indispensable . . . sin agregarse las cargas representativas de intereses comerciales . . ."

Canvassing the Government

Buenos Ayres & Pacific Railway, AGM, October 28, 1937, Lord St. Davids in the Chair:

As to the more distant future of the railway, it does not seem likely to me that until exchange returns to par

anything can put us in the position in which we used to be. There are no signs of any improvement in exchange....

Now I want to speak to the ordinary stockholder, for whom I am frankly very sorry.

He may ask me whether there is any hope for the ordinary stockholder.

Well, as I see it, there is. I have told you that the Government are buying the Argentine Transandine Railway and

you have heard that they are buying other railways. Some of my colleagues do not agree with me, but my own belief is

that it is only a matter of a term of years—possibly it will be a long term of years—before they buy them all.

What is the financial position of the country? The financial affairs of Argentina have been carried on with quite exceptional ability; I think that everyone agrees as to that, and there can be no two opinions about it. They have kept on paying off debt, lowering the interest on their debt and getting rid of liabilities.

Their credit, as you all know, has enormously improved.

What is the position of our finances in Great Britain? I do not think anyone would say that our Government's financial position

is not well managed, but we have got in Europe dangers which are forcing our people to rearm. We have already had to borrow for that purpose, and we may have to borrow over and over again before the process is completed.

This borrowing has put down the prices of our securities and may put them down more. Supposing that this has to go on for another two or three years,

we borrowing and the Argentine paying off and not borrowing, it is quite on the cards that within two or three years the credit of Argentina may be at least as good as that of this country.

If that time comes, will there not be a clamour in Argentina for buying up foreign railways? If that time comes, I think that there will be.

Now look at the financial position of our railway. First of all remember that the Government are buying the Argentine Transandine which is at the end of our line and of the Argentine Great Western. We have a minutely small debt at 4 per cent; all our other money has been borrowed at 4½ per cent or 5 per cent; and our Preference stocks at very much higher

than that, and we are not in a position to get out of the moratorium.

If Argentina chose, it could buy us up by paying off our high-paying debt, and that is where the advantage of our small Ordinary stock comes in.

In a few years' time they might easily buy us up on terms that would pay our debts and leave something satisfactory for the Ordinary stock. That may sound to you far-fetched at the

present moment, but it is right that people in our position should look ahead. Some few years ago a young man told me that he wanted to give his life to Argentine railways.

I said to him "You may find it a very interesting thing to do for the first few years of your life,

but I do not think it will last through your life if you live to be an elderly man because I think

the railways will be bought up," and I think so still. At any rate, these views of mine, right or wrong,

are, I am sure, worthy of serious consideration by anybody who wants to look ahead in South American matters.

(BAP Ry. Co. Ltd., Proceedings ... 1937)

* * *

In the House of Commons:

Sir Nicholas Grattan-Doyle

asked the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs whether he is aware that the permission of the Argentine Government to the Anglo-Argentine railways on 20th December to increase their

rates has been stated to produce £312,000 for the coming year, upon a capital of £270 millions; and, in view of the fact that this increase is insufficient, will he obtain from the Argentine

Government an official statement as to the estimated extent the proposed increased tariffs will benefit the railway revenues?

Sir J. Simon

I assume that my hon. Friend bases his question on a report which appeared in the Press last December that the Argentine Government were about to issue a decree permitting the increase

in railway tariffs which he describes. My information does not indicate that any such decree has, in fact, been issued. His Majesty's Ambassador at Buenos Aires has been requested to

throw any light he can on the origin of the above mentioned report.

Mr. De la Bère

asked the Chancellor of the Exchequer whether, in view of the inability of the directors of the Anglo-Argentine railways to obtain redress from the Argentine Government,

notwithstanding their prolonged efforts, he will request the Council of Foreign Bondholders to take up with the Argentine Government the ill-treatment of the £270,000,000 of British

savings invested in the Argentine railways, and in respect of which His Majesty's Treasury is concerned in relation to Income and Surtax and Death Duties?

The Financial Secretary to the Treasury (Lieut.-Colonel Colville)

My right hon. Friend thinks that the preferable course is that difficulties between the Argentine authorities and British railway companies operating in the Argentine should continue to be

discussed between the British companies and the authorities concerned. His Majesty's Government are always ready to consider any request for support made by such companies. In so far

as the question implies that the Argentine Government's attitude to such companies is one of hostility or that the directors of the British companies have failed to represent adequately the

interests of the British capital invested therein, my right hon. Friend does not agree that such implications correctly represent the facts.

(Hansard, House of Commons Debates, 21 February 1938, vol 332 cc12-3.)

* * *

En sollicitant l'approbation du Congrès pour le rachat du Central Cordoba, le Gouvernement précédent a rappelé les vues qu'il avait déjà exposées dans son premier message quant à l'orientation à

donner à la politique ferroviaire de l'avenir, et tendant d'une manière générale à placer entre les mains de l'État la Direction des services publics essentiels; au cours des débats, qui se sont terminés par

le vote de la Chambre des Députés, le nouveau Gouvernement a manifesté ses dispositions également favorables à cette politique.

Celle-ci ne pourra trouver son application que dans un délai et suivant des modalités que nous ne pouvons déterminer; mais la situation difficile des chemins de fer attire, dè maintenant, l'attention de S.

E. le Président de la République et nous somme persuadés que son Gouvernement saura trouver en temps opportune les formules indispensables pour venir en aide à des entreprises qui ont été crées

pour la mise en valeur du pays et qui doivent demeurer l'instrument essentiel de son développement.

(Compagnie Générale des Chemins de Fer dans la Province de Buenos Aires, Rapport du Conseil d'Administration, Exercice 1937-38, p. 6-7)

* * *

The following statements at shareholder meetings of 1938 all refer to J. M. Eddy's mission to Buenos Aires, from February to December 1938, made to interest the Argentine Government in the formation of a mixed enterprise and gradual nationalisation.

Correspondence on the matter can be found in the National Archives, Kew.

J. A. Goudge, Chairman, Buenos Ayres & Pacific Ry., AGM November 1, 1938:

It is 7 years since we were able to pay a dividend on our preference stocks, and 8 years since the ordinary stockholders received a penny on their investments.... It is not

surprising, therefore, that we are looking forward with great interest, if not anxiety, to the steps the Argentine authorities may be able to take to safeguard their own interests

in the maintenance of efficient railway working. It is obvious that such a condition as I have outlined cannot continue indefinitely. We here can only manifest our confidence

that we shall, as ever before, receive full consideration of our case, and a fair adjustment of our difficult situation.

* * *

Sir Follett Holt, Chairman, Buenos Ayres Western Ry., at the AGM November 2, 1938:

You have no doubt heard of rumours that the Argentine Government is planning a policy for the future of the privately owned railways. With the object of ascertaining the wishes of the Government and

of discovering, should plans be formulated, how far with good will they could be met with mutual satisfaction, our valued colleague, Mr. Eddy, is in Buenos Aires, where he was joined for a time by

Lord Davidson.

Although no concrete proposals have been made, our advices are that there is no doubt that the Government, whilst being anxious to find a means to improve the position of the railways, which is an

urgent necessity for the good of all concerned, is also desirous of evolving a plan to provide for their ultimate acquisition by the State. We can take no exception to a policy of nationalization, as it is our

view that the people of the country who benefit so largely from the railways should at least share in the heavy responsibilities of their finance and risks. (Hear, hear.)

* * *

Sir Follett Holt, Chairman, Buenos Ayres Great Southern Ry., at the AGM November 2, 1938:

You will have heard no doubt of facts and rumours concerning the future policy of the Argentine Government towards the foreign-owned railways. Some general considerations were propounded in the

message that was sent to Congress by the late Government when recommending the purchase of the Central Cordoba Railway, and although some of these must have startled political economists, the

message established the policy of eventual acquisition of the railways by the State.

The position of the Central Cordoba and Transandine systems having been determined, we had reason to believe that the new President and Government, whilst wishing to find means to ameliorate the

position of the other foreign-owned railways, in which Great Britain has such an enormous stake, also adhered to the policy of their nationalization. For us and I maintain for the best interests of the

Republic, the amelioration of the railway industry is an urgent need. It is obvious that those who have invested their money in the industry are not receiving the fair return to which by their courage and

enterprise they are entitled and by their charters they were led to expect. (Hear, hear.)

Although the number of Argentine investors in the private railways is entirely insignificant, the number of Argentines who benefit from their service is enormous, and the railways have reached a stage

at which without improved conditions their maintenance and development must be crippled. For this reason alone, if not in common equity, relief is overdue, for the maintenance of the efficiency of the

railway system remains of vital importance to the Republic, and this leads me to the question of nationalization.

That a progressive and increasingly prosperous country such as the Argentine should continue to depend largely upon foreign genius and wholly upon foreign resources for the care and development of

its main lines of transport is a situation which cannot last for ever. It is inevitable—in my opinion at any rate—that the people of Argentina, through their Government, should at least be prepared to

share some of the responsibilities and the financial risks of the railways upon which their continued progress and prosperity so largely depend. (Hear, hear).

Our colleague, Mr. Eddy, has been in Buenos Aires for some time, and our colleague Lord Davidson, and Mr. Walter Whigham, of the Central Argentine, have also been there to examine at first hand

the trend of events and to aid any plans that may be formulated.

* * *

... the open canvassing of the possibilities of "nationalisation" in the Chairmen's speeches seems to be based in part upon the feeling that company administration of

Argentina's railway systems may never again be rewarded on the pre-depression scale, although the industry justly acknowledges that the Argentine Government today is

showing a keener appreciation of railway problems.

(The Economist, 5 November 1938, page 275.)

The attitude of the Argentine President, Dr Ortiz, towards the financial situation

of the railways was expressed in a recent interview given to Mr J. M. Eddy, who has been

conducting negotiations with the Government on behalf of the British-Argentine Railways.

According to a message from Buenos Aires received by the Anglo-Argentine Press Bureau,

the President stated that the Government were perfectly well aware of the present financial

position of the railways, and that he was prepared to deal with it, but believed that the

problem should be faced and settled in all its aspects.

In accordance with the views already expressed by him on previous occasions, he

was prepared to study a solution which would include transport in general, and in

preparation for which the companies would adapt their financial and technical structure

to present requirements. The intentions of the Government would not exclude the

possibility of State intervention, if this should prove necessary, since the services in

question were public ones which required to be efficiently maintained. In this connexion,

said the President, a suitable fiscalization might be contemplated in order to attain

the end in view.

(The Times, 17 November 1938, page 22e.)

You have heard also that it is a part of Government policy to acquire the

privately-owned railways. However sound this policy of acquisition may be, for the

time being at least it is not expected to be one of practical realisation, except

maybe in certain zones where the State Railways are already heavily involved as they

are in Entre Rios. ...

Owing to the publicity that has been given to it, I must take this opportunity to

refer to the communication from an official source which appeared in "The Times" and

no doubt other newspapers on Thursday last. It gave the text of a communication that

had been made to Mr Eddy by the President of the Republic a short while ago for the

information of the Boards of Directors of the British-owned railways who were at the

time meeting their shareholders.

The message was received, substantially as reported in "The Times," and was

considered with grave attention by the Directors concerned but was not announced at

the meetings as it was thought that the questions which would have been raised might

have caused mis-apprehensions and misunderstandings amongst the Stockholders,

which it was our ardent wish to avoid. I need hardly say that the message, with which

we were honoured, is receiving and will receive, the full attention it demands and

deserves.

(Sir Follett Holt at Entre Rios shareholders' meeting, 21 November 1938.)

In the House of Commons:

Sir Nicholas Grattan-Doyle (Newcastle upon Tyne North)

asked the Prime Minister whether, in view of the failure of the London boards of the Anglo-Argentine railway companies to earn more than 2¼ per cent. on £277,000,000 of railway

capital, of which £144,000,000 has not been allowed to earn a dividend for some years past, he will propose to the Argentine Government that they should buy the Anglo-Argentine

railways at a price of their cost to British investors in return for Argentine Government sterling bonds or, alternatively, that the Argentine Government should relax the restrictions

imposed upon the companies so as to allow them to earn a dividend of not less than 5 per cent. on the £144,000,000 of capital?

Mr R. A. Butler (Saffron Walden)

According to a recent statement from an authoritative Argentine source, the British companies concerned have submitted to the Argentine Government various suggestions for reform

tending to remedy the situation, and the authorities are examining these with all good will to find an equitable solution within reasonable limits. His Majesty's Government, who are

naturally interested in the welfare of the railway companies concerned, welcome this statement. The Argentine Government are already aware of the hope of His Majesty's Government

that a settlement satisfactory to both parties will be reached as soon as possible, and my hon. Friend may rest assured that His Majesty's Government will continue to watch the situation in

full consciousness of the importance of the British interests involved.

Mr Emanuel Shinwell (Seaham)

Can we have an assurance that we shall not have a quarrel with the Argentine Government, such as we had in the case of Mexico?

Mr R.A. Butler (Saffron Walden)

I do not think the cases are similar.

(All Commons debates on 21 Nov 1938.)

A Project for the Nationalization of the Railways

PRESENTED BY NATIONAL DEPUTY JOAQUÍN MÉNDEZ CALZADA

The following is a free translation of a draft law presented to Congress by National Deputy Joaquin Méndez Calzada (Partido Demócrata Nacional, i.e. conservative governing party,

Deputy for Mendoza 1938-1942) providing for the purchase by the State of all or part of the privately-owned railways in the Republic:—

Article 1.—During the term of two years from the promulgation of the present law, the Executive Power of the Nation is authorised to concert with such railway companies as resolve to

avail themselves of the benefits of the same and ad referendum to the Honourable Congress, the sale and transfer to the Nation of their lines and instruments of transport on the general

conditions therein established.

Art. 2.—The agreements shall comprise the transfer of the movable and immovable properties situated in the Republic which form part of their investments and assets, as verified by the

Dirección General de Ferrocarriles and which are proper and inherent to the services of transport.

Art. 3.—The transfers may be concerted for global prices on the capital actually invested

and already recognised by the Dirección General de Ferrocarriles and the National Executive Power, and up to a price which shall not exceed sixty per cent of the total capital invested; or,

likewise, on the basis of percentages on the amount of their distinct obligations in debentures and preference and ordinary shares, in which case the partial percentages must not exceed the

margin of ten per cent. on the average of the official quotations attained by the different categories and share capital (debentures, first and second preference shares, ordinary shares) on

the London market during the period 1927 to 1937, always provided that the general average of the purchase price and conversion does not exceed the 60 per cent. already referred to, on

the recognised capital.

Art. 4.—For the carrying out of the operations contemplated by the present law, the issue is authorised of up to 650 (six hundred and fifty) million pesos gold, or its gold equivalent in

foreign currencies, of bonds to be denominated Obligaciones de los Ferrocarriles Argentinos del Estado, divided into three series of 3½, 4 and 4½ per cent., with 1 per cent amortization

annual and cumulative, with a quarterly service, and to which would be assigned the general revenues of the State railways, both from their own system and from the systems incorporated

in it. The Executive Power is authorised to fix the amount of each issue and series, as also the monetary currencies of each, within the maximum figure authorised.

Art. 5.—To fix the global prices or the percentages on the different classes of obligations and share capital, the Executive Power will formulate a proportional scale, relating price bases

which represent between 40 and 60 per cent of the capital invested, to the average of the liquid working yields of each company in the period 1927-1937, which shall be taken as the basis

to establish the one or more percentages corresponding to each conversion, as also to establish the type of series and the interest to be agreed upon. The agreements may comprise the

payment in bonds of different series and interest rates, whether the negotiation be effected on the basis of the fixing of percentages on the different obligations and shares, or for global

prices. Bonds of the Series "A" of 4½ per cent. cannot be assigned to companies which have not attained a liquid yield of 4 per cent. as a general average during the period, but they can

be assigned to convert debentures of a higher rate of interest in the case of agreements based on partial percentages on the different obligations and shares. Nor can bonds of Series "B" of

4 per cent. be assigned to companies which during the same period show profits below 3½ per cent. Bonds of Series "C" can be utilised for the payment to those which have not attained

those averages or which have shown no profits.

Art. 6.—If on the expiry of the term of two years fixed by Article 1, the issue authorised by Article 4 has not been totally utilised or pledged, owing to any railway company not having

accepted the conditions of this law, the authorised amount of the issue will be understood to be reduced to the limit of the sum pledged.

Art. 7.—The companies and the Executive Power shall agree as to the procedure and the occasion for the transfer and handing over of the lines, rolling stock and other properties, which

would at once be placed under the control of the Administration General of the Slate Railways which, once in possession of the new lines, would proceed, within a period of six months

and after the approval of the Executive Power, to effect the unification of the general tariff of transport for the whole of its system and to formulate and apply a plan of rationalization of

the services and costs of working.

Art. 8.—The whole personnel of the entities transferred would come under the dependency of the Administration General of the State Railways, with the exception of the directing or

administration staff of the private companies whose services were not found necessary.

Art. 9.—Let this be communicated, etc.

(Signed) JOAQUÍN MÉNDEZ CALZADA.

(The Review of the River Plate, 1 July 1938, pages 10-11.)

The British proposal:

In October 1939, Baring Brothers & Co. put forward a plan for the nationalisation of the British-owned railways.

In June 1940 the Governor of the Bank of England wrote a letter to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, suggesting that

new large-scale purchases of Argentine maize be made on condition that the Argentine purchase the railways on the basis suggested by Barings.

That basis was similar to the Pinedo Plan and to the terms of the Miranda-Eady Agreement.

The Governor's proposal was discussed in various ministries and departments but did not prosper.

Political advantage gained by selling railways did not justify purchases in excess of immediate requirements.

Nacionalización de los ferrocarriles particulares

Últimamente se ha divulgado que el Poder Ejecutivo de la Nación presentaría al Parlamento un proyecto tendiente a nacionalizar los ferrocarriles particulares, lo que parecería ser una

definida determinación gubernativa de próxima realización, por las disposiciones consignadas en el "Plan de Reactivación Económica" ya aprobado por el Senado Nacional.

Por lo tanto, y con la finalidad de promover su estudio por los técnicos argentinos, hemos considerado oportuno ocuparnos de este complejo e importante problema actualizado por la

difundida mala situación financiera por que atraviesan las empresas ferroviarias particulares que, de prolongarse, afectará a sus servicios, y con ello al desarrollo normal de la vida

económica nacional.

De ahí que se hayan realizado algunos estudios sobre los ferrocarriles de capital privado, entre los que se destacan la monografía recientemente publicada por el Instituto de Economía de

los Transportes de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de Buenos Aires, y el informe divulgado últimamente, y que fuera preparado, hace algún tiempo, a pedido de varias empresas

interesadas.

La excelente monografía del referido Instituto oficial abarca tanto el examen y análisis de la situación económico-financiera de los ferrocarriles particulares en el período 1928-1939 como

el estudio del costo y precio de los transportes ferroviarios en nuestro país, e incluye una investigación sobre la posibilidad de que el Estado adquiera y explote esas líneas férreas.

Por su parte, el otro estudio persigue la formación de una entidad denominada "Corporación de Ferrocarriles Argentinos", tendiente al traspaso progresivo al Estado de las líneas

ferroviarias particulares.

Ambos trabajos tratan de obtener en forma distinta la estatización de esos ferrocarriles, pero descartando en absoluto la compra basada en la tan debatida cuenta capital, que según las

empresas al 30 de junio de 1938 ascendería a casi 3.268 millones de pesos moneda nacional, mientras que de acuerdo al decreto del Poder Ejecutivo del 30 de junio de 1937 sería de 2.866

millones de la misma moneda.

Por eso y por el estado de las instalaciones y del material rodante, nadie ya pretende que la nacionalización de los ferrocarriles particulares se haga aplicando el artículo 16 de la Ley

Nacional 5315, cuyo primer párrafo dice así: "La Nación se reserva el derecho de expropiar en cualquier tiempo las obras concedidas por el monto del capital reconocido aumentado en un

veinte por ciento".

El Instituto de Economía de los Transportes, después de diversas consideraciones, llega a mostrar que seria factible a nuestro gobierno la adquisición de los ferrocarriles particulares, con

la emisión de un empréstito por un monto aunque sea igual al 100% del capital reconocido, con interés del 4% y amortización del ½% durante 56 años, en mérito a que el promedio anual

de las utilidades durante los once años del período 1928-1939, ha sido de 112,6 millones de pesos moneda nacional.

Por su parte en el plan elaborado por encargo de las Empresas de los Ferrocarriles Sud, Oeste, Central Argentino y Pacífico, se encara la nacionalización progresiva y de acuerdo a las

disposiciones esenciales siguientes: constitución de una sociedad anónima por acciones sin valor nominal determinado, a la que las empresas mencionadas entregarían todos sus bienes, la

que cargaría con "el pasivo privilegiado de las compañías reducido en su monto y en su interés a 131.496.498 libras esterlinas de debentures a cargo de la nueva entidad, todos ellos del 4

por ciento de interés y ½ por ciento de amortización acumulativa"; supresión de las rebajas que por ley le corresponde al Gobierno Nacional para sus transportes y que se aprecia en el

promedio anual de 13 millones de pesos moneda nacional, lo que significa una contribución fiscal por esa suma como mínimo pues es lógico esperar una creciente actividad del Estado;

emisión de acciones A y B, las primeras por el 70% del patrimonio y las segundas por el 30 % restante, que se entregarán al Estado

si acepta todas las estipulaciones, en cuyo caso le corresponderá el Presidente y el 30 % de los directores de la Sociedad; separación de las utilidades anuales de 38 millones a prorratearse

entre las compañías y de 18 millones para el Gobierno Nacional, y el excedente, si lo hubiera, se repartirá en idéntica proporción; formación de una reserva por un importe igual a la

cantidad requerida para abonar los dividendos, durante un año, a las acciones A y B; amortización de las acciones A, con la

aplicación parcial de las ganancias obtenidas por las compañías, pero supeditándola a determinados porcentajes y condiciones; y garantía subsidiaria de la Nación para el cobro de los

dividendos por accionistas y prestamistas. . . .

(firmado: J. A. V., La Ingeniería, año xliv, No. 794, diciembre 1940, p. 1021-1022.

Un plan parecido fue discutido en comisión mixta argentino-británica durante los finales del año 1943.)

PROPOSED ARGENTINE RAIL PURCHASES

The purchase of the Entre Rios and Argentine North-Eastern Railways by the Argentine Government

was proposed in a bill submitted to the Chamber on January 13th by the Conservative [not any

Socialist] members for the Province of Entre Rios. An essential feature of the scheme is that the

price must not exceed 61.3 per cent. of the capital computed [recognised] by the Direction-General

of Railways.

The deputies in question regard the proposed purchase as another step towards the fulfilment of the

plan for the nationalisation of all the railways, announced by President Justo when he submitted the

Cordoba Central and Transandine bills to Congress.

The project authorises the Government to enter into an agreement with the companies for the

purchase of their track, rolling-stock, fixtures, etc., under conditions similar to those established in

the case of the Cordoba Central line.

The percentage of the computed capital mentioned above is to be the purchase price, provided it is

lower than the present value of the assets, after deducting depreciation. For the purchase of the

material stores of the railways, the bill fixes the sum of £198,254 for the Entre Rios and £82,402 for

the Argentine North-Eastern lines, subject to assessment.

The bill also authorises a bond issue, bearing interest at 4 per cent. per annum, with an annual

accumulative sinking fund of 1 per cent. to cover the cost of the operation, while any amount that

may be required to be paid in cash under the terms of the agreements may be taken from general

revenue.

The bill will not come up for consideration before the ordinary Congressional period starts next May.

Issued capital of the Entre Rios Railways Co. is £4,517,189, and outstanding debentures total

£4,405.000. The Argentine North-Eastern Railway Co. has an issued capital of £2,768,500 and

debentures outstanding amount to £4,623,190.

(The South American Journal, 28 January 1939, page 106).

[The capital recognised as of 30 June 1938 was $83,144,631 m/n for the Entre Rios and $89,671,973 m/n for the

Argentine North-Eastern. At $16 per £, that amounted to £5,196,539 and £5,604,498 for the ER and ANE railways. 61.3

per cent of that would have been £6,621,036. Add £280,656 for stores, and the 4% interest on the £6,901,692 total

would have amounted to £276,068 per annum. Compare that with the total interest paid by the two companies during

1937/8, £155,470, after which substantial arrears of interest remained and no dividends had been paid for several years.

How the Deputies arrived at their figures for stores is unclear. Balance sheets for 30 June 1938 and 1939 showed stores in hand and in transit

of the Entre Rios Railways of £227,811 and £253,558, and of the Argentine North Eastern, £102,005 and £104,995 respectively.

S.D.]

More on this:

PROJECT FOR PURCHASE OF ENTRE RIOS AND ARGENTINE NORTH EASTERN RAILWAYS

Last week, National Deputies Morrogh Bernard, Padrós, Labayén and Medina, presented a project to Congress for the purchase by the State of the Entre Rios and the Argentine North

Eastern Railways.

We imagine that the project need not be taken very seriously at this stage. The following is a free translation of its text:—

"The Executive Power is hereby authorised to concert with the owning companies, the acquisition of the Entre Rios and Argentine North Eastern Railway lines with all their installations

and dependencies, subject to the bases and under the same financial conditions as were agreed upon for the acquisition of the Cordoba Central Railway system.

As the maximum purchase value, in pounds sterling and at 4 per cent. interest and one per cent. amortization, there is hereby fixed the proportion of 61.3 per cent. of the capital reckoned

by the General Railway Board as the physical assets of the aforesaid companies, always provided that that sum proves to be less than the actual value of the said assets, after deducting

such depreciation as may affect them.

The Executive Power is likewise authorised to acquire the existing materials in stock, pertaining to the said railways, within the maximum sum of 198,254 pounds sterling for the Entre

Rios Railways and 82,402 pounds sterling for the Argentine North Eastern Railway, subject to result of their valuation.

The Executive Power is hereby authorised to issue bonds of Crédito Argentino Interno of 4 per cent interest and 1 per cent. amortization, cumulative, or to utilise the sum necessary out of

general revenue, as an advance, for the payment of the cash quota that may be agreed upon and for other expenses the operation may involve. The Executive Power is likewise authorised

to issue bonds denominated Bonos de los Ferrocarriles del Estado for the payment of the remainder of the price agreed upon, the interest and amortization services of which shall be

attended to by the State Railways, with the guarantee of the Nation.

The Executive Power is hereby authorised to arrange with the Argentine North Eastern Railway for the repayment of the sums received by that company in terms of Laws Nos. 3,350,

5,000, 6,370 and 6,508."

(The Review of the River Plate, 20 January 1939, page 16.)

The last paragraph above is particularly disingenuous. Law 3350 was passed in 14 January 1896 to do away with the guarantee system and settle the amounts owing by the National

Government under previous concessions and contracts. By Laws 5000, 6370 and 6708 the ANER received grants to facilitate its extension to Posadas, its connection with Paraguay at

Posadas, and its extension to Concepción del Uruguay. The amounts granted under these laws were not repayable unless the railway earned more than a specified percentage of its capital,

which it never did. Moreover, the amounts received in grants under laws 5000, 6370 and 6508 were never included in the capital cost of the corresponding works reported to shareholders

and were already excluded from the amount of "recognised capital" which the legislators were not prepared to pay. In short, this project of law is a perfect example of the then current

predatory attitudes taken in Argentine official circles.

The promoters of this predatory law were not ignorant of equitable business principles. Juan Francisco Morrogh Bernard was born in Gualeguaychú 29 March 1894, elected deputy in

1932 (Partido Demócrata Nacional), was first Vice-President of the Chamber of Deputies, died in car crash at Curuzú Cuatiá 29 August 1969. Representing Tucumán sugar interests,

Julio Simón Padrós was elected on the conservative ticket of the Concordancia. Juan Labayén and Justo G. Medina had been members of the Entre Rios Constitutional Convention of

1932; Labayén was president of Frigorífico Gualeguaychú. Justo G. Medina was a journalist, editor of El Demócrata, elected to Congress in representation of the Partido Demócrata